One of my favorite things about going to Crete is the grand variety of caves. This may come as a bit of a shock to those who know me best, as I make no pretense about having a healthy respect, (i.e. a borderline fear) for caving. Nothing gives me pause quite like the thought of finding myself wedged between a small gap between two rocks miles and miles under the dark, damp earth. However, the cave experiences I’ve had in Greece are the kind that are walkable and open, and dare I say ‘breathable.’ In Crete, I can act like a tourist paying my respects to the bowels of the earth, a visitor who dips their toes into caving without the risk of bodily injury. It is a quintessential outdoors activity.

There’s no greater place to enjoy some ‘relaxed’ caving than Crete. The island is dotted with so many wonderful places to explore, and I’ve already touched on one of the best-known caves, Diktaion Andron in the Lasithi Plateau. All of the caves on Crete are seasonal; they open in April and close in October, as the rains and snow make exploring the caves too dangerous. But once spring rolls around, tourists like me are free to explore these natural wonders. Some of these caves have guided tours while others are self-exploratory paths. These caves are protected as national monuments by the Greek Government, so if you choose to visit these caves, it’s best to go in with a respectful mindset, of not only the rules that are in place to protect the health of the cave, but as well as the history it represents.

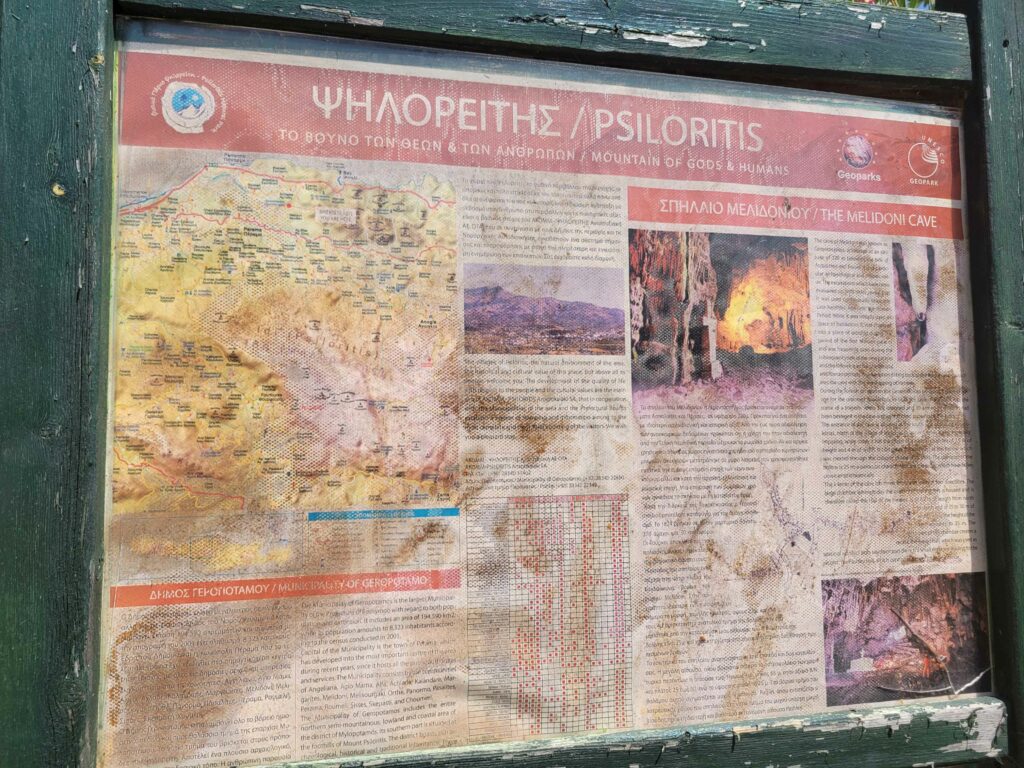

This brings me to the beautiful Melidoni Cave, which can be found on the way to Rethymno and 1800 kilometers from the village that shares its name. Should you decide to go, I would advise you to be careful on the way to the village and take that last stretch of the A90 slightly slower so you don’t miss the turn, and be forced to drive your slightly-too-large grandfather’s car through the streets of tiny villages that aren’t your destination. If you miss said turn, which I must admit is easy to do, you can trust the maps to redirect you and perhaps see a lesser explored part of Crete. Passengers who accompany you, however, will be more prone to screaming if you happen to follow the GPS through a tiny village with even tinier side streets. As your side mirrors are pushed inward, the village cats watch you with a mixture of caution and disdain from the steps of homes you are praying your car is thin enough to squeeze between.

This may surprise you, but it was I, gentle reader, who found myself wedged in that uncomfortable predicament. If Melidoni cave was one of those caves in which explorers had to wedge between rocks, I might have taken my mistake as an ill omen, but I followed the road safely out of the small villages with little to no discomfort. Using the GPS with slightly more attention, I found my way to the town of Melidoni without incident, relishing normal roads. The 2km road leading out of town and up the mountain to where the cave awaits is a beautiful expanse 200km above the valley, which results in a splendid view the entire valley, which in the spring colors the valley in flowers that disappear come the summertime.

All one must do upon their arrival is pay the €4 ticket fee (€3 for children) to enter into the garden path beyond the café. I took my time on the short walk up the path to the mouth of the cave, savoring the dappled light that filtered through the tall trees that rustled softly in the breeze. It felt, to me, like it was the last kiss from the outside world before I descended into the mouth of the cave. As I neared it, the path in question became less woodsy, as if the last concentrated area of sunlight was something I was meant to savor before my descent.

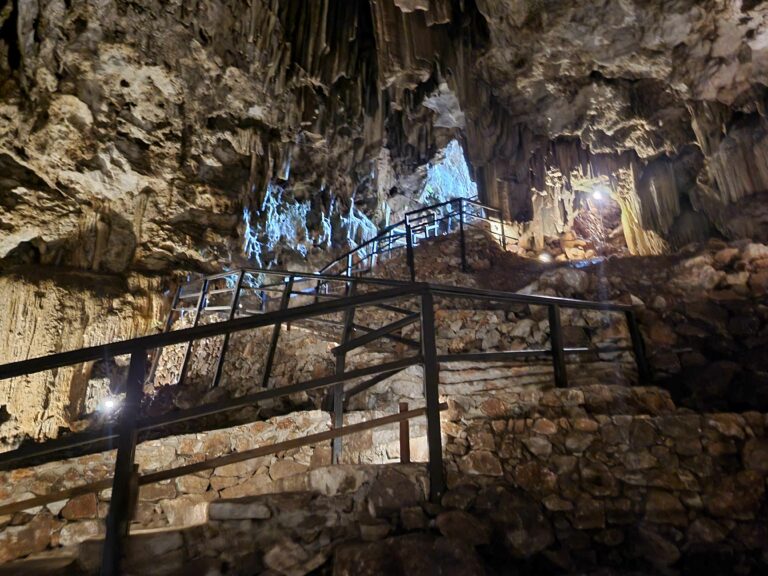

The stairs in Melidoni Cave were very well managed, and not nearly as steep or long as I have experienced in other caves. It was, in fact, one of the safest set of stairs I’ve been on when entering a cave in Crete, and though I took my time, I felt sure-footed most of the way down. I went to visit the cave during the height of summer, so the drastic temperature change from almost 100°F to roughly 75°F was a welcome relief from the Cretan sun. The stairs led right to an almost cathedral-like main room with an altar right in the center of it, stalactites hanging from the ceiling in in an arch-like fashion that only added to the majesty and imperial nature of the cave. All along the floor were small electric lanterns that gave the place the sensation of being inside a chapel rather than in the bowels of the earth, and a reverential hush fell over all of us who entered. I decided to explore the surrounding walkways before making my way to the obvious focal point of the stone altar, and took the pathway to my right.

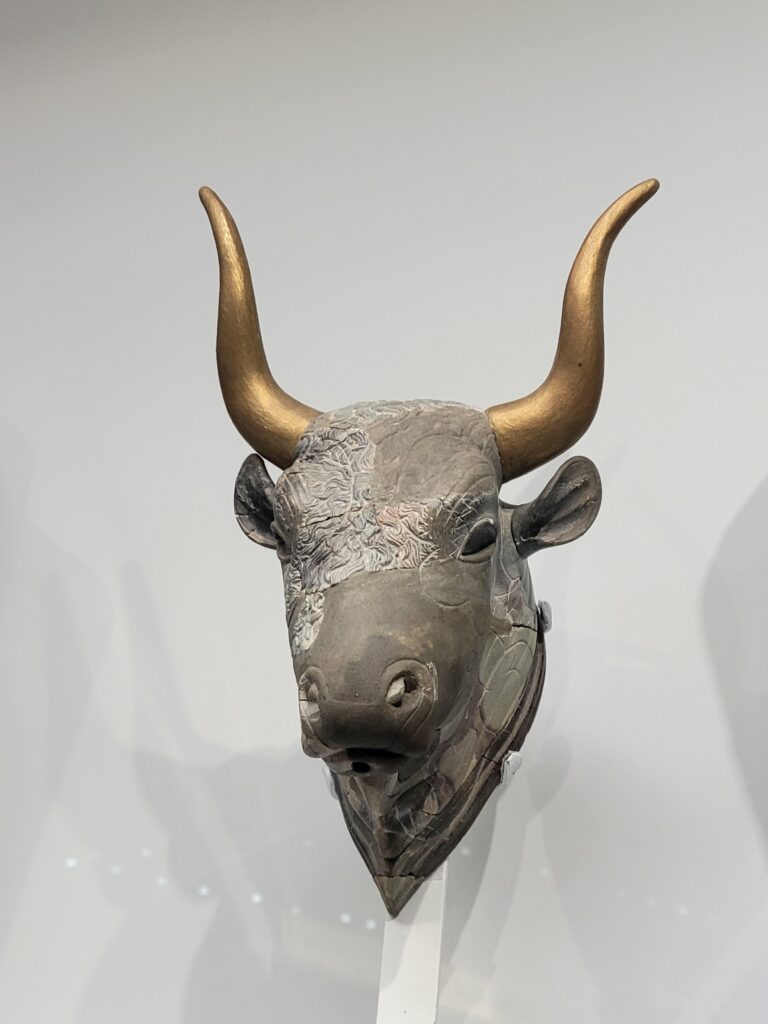

If you check the website for the cave beforehand, you’ll see many references to the worship of Talos. For those not in the mythological know (or those who never say Ray Harryhausen’s depiction of him in the 1963 version of Jason and the Argonauts), Talos was an automaton crafted by the god Hephaestus. Made entirely of bronze, it was said that this giant robot served as protector to the island of Crete, and was worshipped by the ancient Minoans. This was when the cave was known as Gerondospilios, rather than by Melidoni.

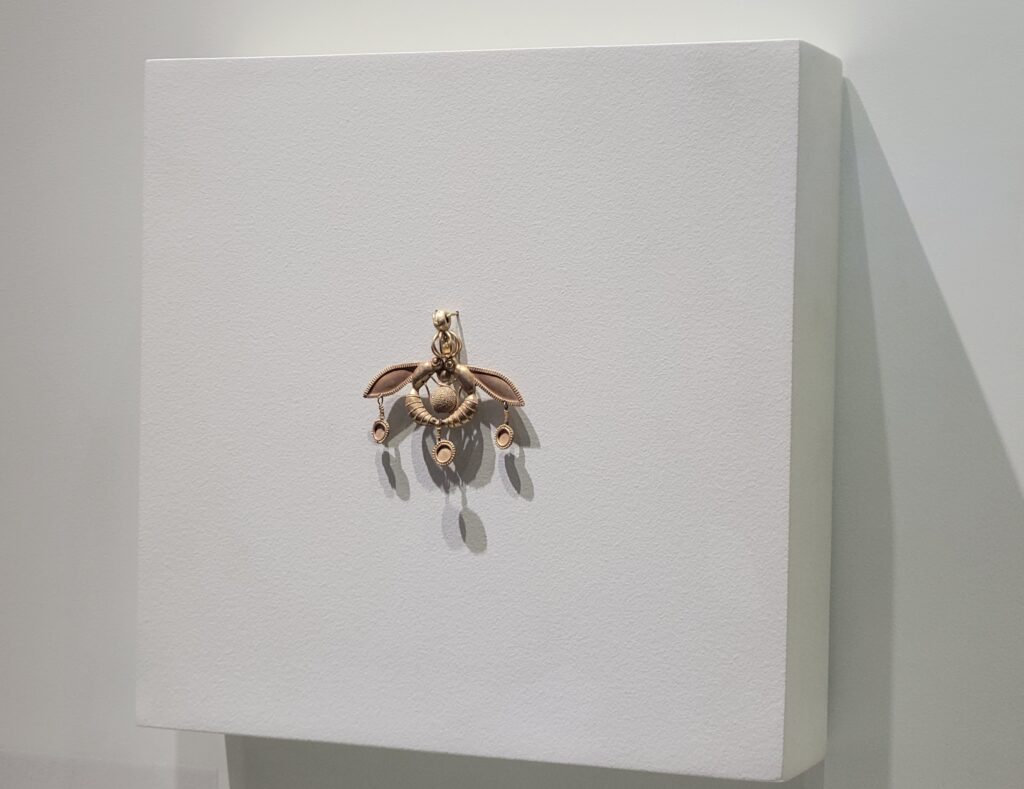

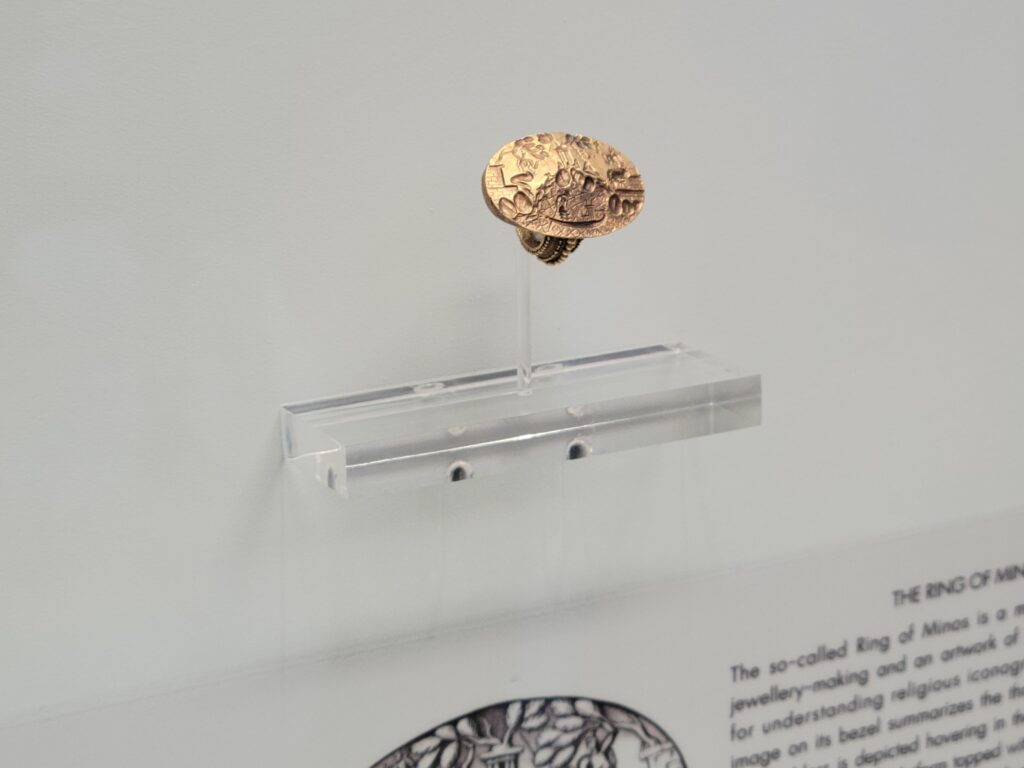

Of course, the cave served many purposes besides a meeting place for the worship of Talos. All along the cave walkways were informational plaques that told of the vast archaeological discoveries within the cave. The people of the bronze age used to use caves for refrigeration, storage, cooking, and shelter, and so many bronze age artifacts were uncovered here. Most of the artifacts are on display in the nearby archaeological museum of Rethymno for the public to view. The cave also has a distinct tie to the worship of Hermes, as inscriptions (i.e. ancient graffiti) on the cave wall make reference to the cult of Hermes, even up to the period of venetian and turkish rule of the island. The cave calls these inscriptions the ‘book of visitors,’ as many who came to pay respects left their names upon the wall. Worshippers seemed to address the messenger god as Hermes Talaios, though I am unsure as to why he received the additional moniker.

Following the pathway around the ‘Room of Rocks’ and towards the ‘Stone Curtain,’ I slowly made my way back around to the initial room, marveling at how the carefully placed lights made the room such a hauntingly beautiful place, the shadows against the stone walls resembling a kind of drapery. Finally, I was ready to approach the altar that served as the focal point of the cave, and read the plaque that told me why such a thing existed inside the cave. It was not, as I had first assumed, because the cave had been used as a place of worship: it was, in fact, a place of refuge. In 1823, during the war for independence from the Turkish forces, 370 women and children, as well as 30 resistance fighters, ran to Melidoni cave for refuge from Hussein Bey, the leader of the Ottoman forces at the time. The escape plan resulted in those 400 people becoming trapped inside of Melidoni cave with nowhere to run, which was good news for Hussein Bey; if he could starve them out, he would get a complete surrender, dealing a blow to the resistance movement. The problem, of course, was that he was dealing with the people of Crete: their answer to his request was “Death, no surrender.”

Hussein obliged. He ordered his troops to light fires at the cave entrance and then blocked it off, sealing the people inside with no oxygen and a growing, suffocating cloud of smoke. All 400 people perished within Melidoni Cave, perhaps, I realized, on the very ground I had been walking on earlier. Egyptian troops, whose stake in the war was to assimilate Crete into Egypt, arrived days later and desecrated the corpses. However, the bodies of the fallen resistance leaders and the 370 women and children were cleaned, and their bones were put into the ossuary that I had originally mistaken as the central altar.

The stone above me, in front of me, below me and to all sides suddenly felt a little too close as I imagined this being a final resting place. With the lights in the floor and the sunlight leaking through the mouth, the cave was beautified, almost peaceful. I tried to imagine it dark, with the doors closed to me, with smoke filling my lungs. It was not so peaceful then. But I suppose that is the power of memorial: we take the places of great tragedy and turn the wounds of the earth into scars, as healed as we can make them. We try to give those who perished alone and afraid into a place that they might find restful. We leave on the light in a place where women, children, and fighters died alone in the dark. Maybe it isn’t much. But the quiet reverence of the cave, palpable from the second I set foot on the stairs, was perhaps the only way left to visitors like me to honor them.

I made my way out of the cave, like Orpheus departing from the underworld, step by step. Like Orpheus, I turned to look back one final time before I had made it completely out of the cave, staring at the altar in the dark as it was gently lit up by the lanterns on the floor of the cave. I thought about those who could not leave, and all the visitors across millennia, like myself, who could. I thought about how this cave had been in the service of this island for thousands of years, and how even now it served us by teaching us about those who came before, those who used the cave as a place of worship, comfort, and all the aspects between life and death. I passed out of the cave and into the sunshine once again and breathed in deeply. The air was sweet and hot and I was glad of it all.

I thanked the cave for all that it had been, and left to see what else the day had in store for me.

By Katarina Kapetanakis