It has been famously stated that, while ‘poems are made by fools like me/only God can make a tree.’ This is a truth so obvious it almost doesn’t need to be said. I, ever the poet, languish on my silly little travel blogs while God divinely calls forth mighty oaks from saplings, or great pine trees from tiny cones. I’m not envious, really. He sticks to what he does best and I stick to what I do best and we all get along swimmingly. As a result of the divided labor, however, trees were never at the forefront of my consciousness.

That’s not to say I never spared any of my thoughts for the trees. In my youth, my father spent a great deal of his time (and, as a result of my status as child, my time) at plant nurseries, finding the most beautiful trees to plant and rear with love and care in our growing garden paradise. While I was supportive of this in the abstract, I had no real desire to join my parents in the hard work of actual gardening. In my mind, the Florida sun was only fun if I was at the beach, a theme park, or doing some sort of activity that was catered to…well, me. Though I was often enlisted to assist against my will, nothing about hard work in that heat appealed to me. While I can look back on those memories with a relative fondness, today I am content to live in an apartment where I barely remember to water my little cactus once a month.

My childhood instilled in me a respect for trees, even if I don’t go out of my way to cultivate a green thumb. I’ve helped plant them, I’ve harvested fruit from them. I’ve watched my parents work tirelessly to attempt to save sickly ones, transplanting trees delicately from one part of the yard to the other in an effort to give it more sun or more shade. I grew up with the constant reminder that deforestation was a legitimate issue, with campaigns to save the rainforest everywhere there was an iota of environmental awareness. Save the Trees! Plant a Tree! Hug the Trees, Kiss the Trees, Speak for the Trees! Trees faded into the background of my life as a nice thing to appreciate during walks in the evening or strolls through a botanical garden, but they did not occupy much space in my thoughts besides. They gave me oxygen, I took them for granted.

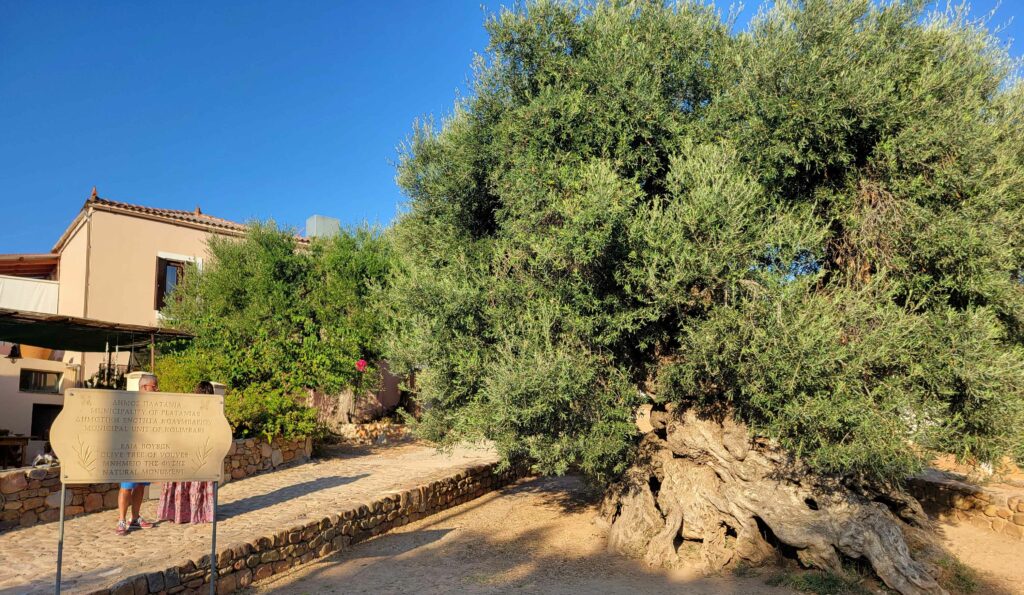

But on the island of Crete resides a very special tree. I had heard about it in passing, a small factoid dropped in an otherwise casual conversation, but it struck me as such an odd thing to consider ‘casual.’ To be told that one of the oldest living trees in the world currently lives and breathes only 146 kilometers from the villa you’re vacationing in sounds like a bombshell. Something about being in the presence of a practical immortal filled me with curiosity, and I made a point to see with my own eyes the Ancient Olive Tree of Vouves.

The Olive Tree of Vouves is not, as I first thought, the oldest living tree in existence. This honor belongs to Methusela, a Great Basin Bristlecone Pine tree that resides in the White Mountains of California. If we factor in the different types of trees such as clonal colonies, angiosperms, gymnosperms, and a million other words that I learned just to write this cursory sentence, you’re going to have a difficult time narrowing down just which tree you want to visit. But the Olive Tree of Vouves is estimated to be the oldest living olive tree, and on a place like Crete, that is no small thing. Olive trees are nourishing. Their fruit has sustained civilizations upon civilizations, from the days of the Minoans to the modern day. Their wood is beautiful, and when treated right, makes furniture that lasts. Their branches have come to not only represent victory, such as when crowns made from their branches were woven into crowns during the Olympics, but also as a symbol of global peace. Of all the trees to survive the test of time, it is the olive tree to keep persisting.

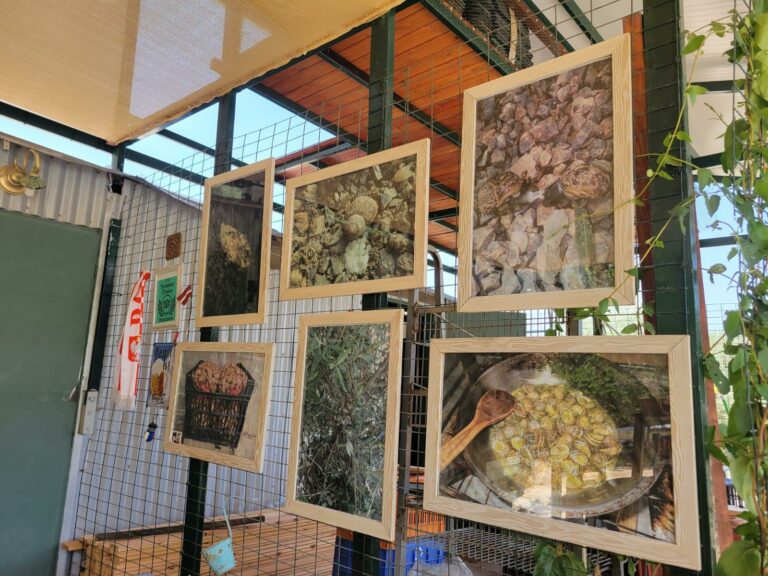

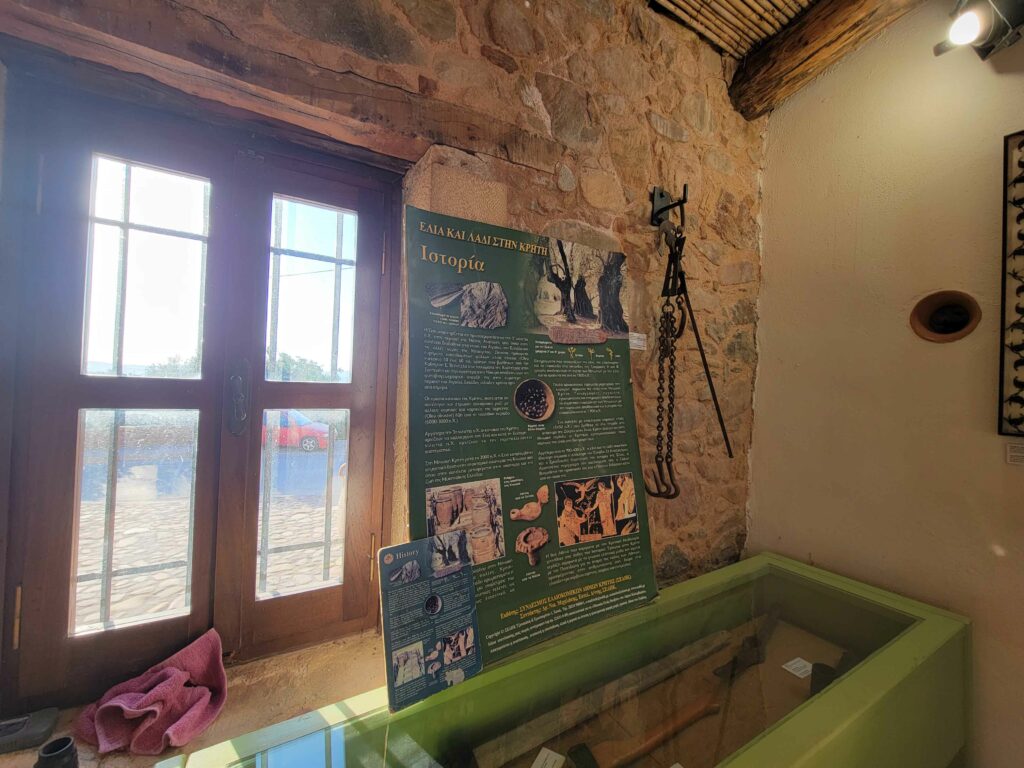

The tiny town of Ano Vouves a little ways west of the city of Chania. The winding roads are surprisingly easy to navigate, and though at times you are required to pass through the villages carefully, it isn’t hard to reach. You see the tree before you even come to a complete stop, unable to miss the gargantuan trunk and mass of branches. Parking is easy, right in front of the tree itself, which is good because once you’ve made it there, it’s difficult to look at anything else. Around the tree, the buildings all cater to the celebration of The Olive, from a tiny museum related to how olive harvesting was carried out, to olive oil-based products, and even a café that sells ice cream and olive oil products, all from those olives harvested by a tree in the center of the square. This is the oldest olive tree in all the world, though the signage indicates we cannot be more precise. We are able to place the tree anywhere between 2,000-4,000 years old, but cannot test for sure due in part to both the age of the tree and the fact that the heartwood, the thick center of the tree, is no longer present. Scientists at the University of Crete are responsible for giving us as close of an age approximation as we have.

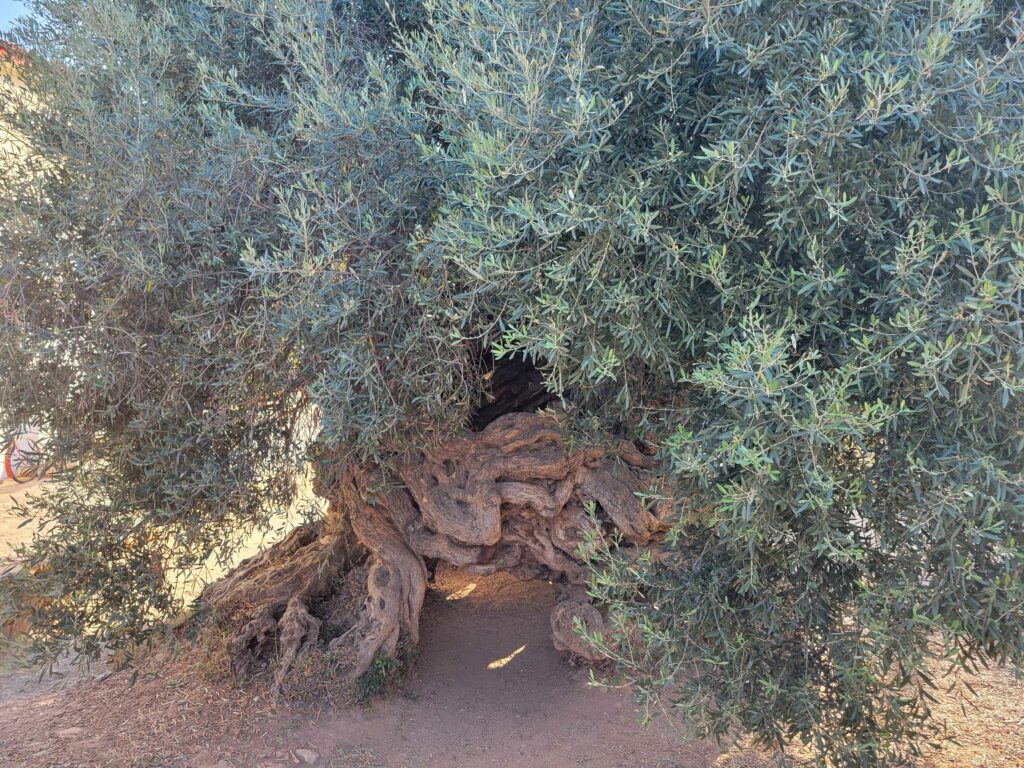

The tree itself is a great, imposing thing, almost akin to a great sleeping god rather than tree. It is within a dirt patch, with bricks creating an ankle-height wall around it. It is thick, its’ knotted wood twisting and knotting in great patterns across its’ trunk stretching into the ground like thick legs. It gives the impression that at any time, this hulking beast of a tree could uproot its’ mighty legs and walk away. It is perhaps the thickest olive tree I’ve ever seen, almost 15 and a half feet in diameter, and yet the only olive tree I’ve seen that is hollow at its’ center. Instead, if you’re so inclined, you can peek through into the center of the tree, stepping into another world of dappled light, bugs, and the sound of a breeze wafting through the leaves. It is almost as if the tree body has become a living temple to nature, complete with a choir of cicadas singing hymns to olives.

I touched the tree, and touching a living thing that was old enough to be domesticated by another civilization astounded me. It was like touching something holy, and in many ways I suppose I did touch something holy. What is holier than a tree that fed and nourished not just the Greeks, but the Minoans before them? One of the first wild olive trees to fall tame to the hands of man, outlive them all. Still it lives. Still it breathes. Still it grows its’ roots into the Cretan earth, still it produces olives for the locals of Vouves to take, to grind oil from it, to take care of the tree in return.

When I visited the tree, there were children playing all around the square. I wondered if it must have always been like this, the sun shining down on this great tree as it watched the world around it live, running about just like the ants about its’ branches. I wondered if it could feel my touch, what level of awareness such a thing like that could have. I wondered if it was, perhaps, the oldest living thing, let alone tree, in all of existence. I wondered what all of that meant.

I was not there for longer than perhaps an hour. I stayed for some ice cream and watched the tree from the covered patio as I ate, listening to the cicadas, feeling the breeze on my own skin. I smiled at the sound of a tourist train coming to fetch passengers to other places, possibly to Chania which was only 30 miles away. The sunset was coming, and with it the beloved Golden Hour all photographers chased, and I felt that the tree was more beautiful than anything I’d ever seen in my relatively short life. I would be a blip, if that, in the lifespan of this tree. I would not even be a memory, if trees are capable of such a thing. But the impression that this giant of branches, leaves and wood left upon my mind is set in stone. I felt a peace I’ve only felt in the halls of forgotten churches, in quiet cemeteries, in hallowed ground.

If only God can make a tree, he certainly knocked it out of the park with this one.

By Katarina Kapetanakis