It’s almost Valentine’s Day and love is in the air. Pink and red hearts dot the counters at the grocery store, candy hearts and teddy bears sit expectantly in the aisles for the boyfriends who put off shopping too long. Assorted boxes of chocolates, some better than others, are stocked on shelves, and couples everywhere eagerly book reservations for date nights they’ll be sure to remember. We love to celebrate Love with as much gusto as the emotion evokes…so how do we celebrate love in Greece? This Valentine’s Day, let’s dive into some of the more romantic traditions and myths of the Greek people just in time for a candlelit dinner.

Cupid

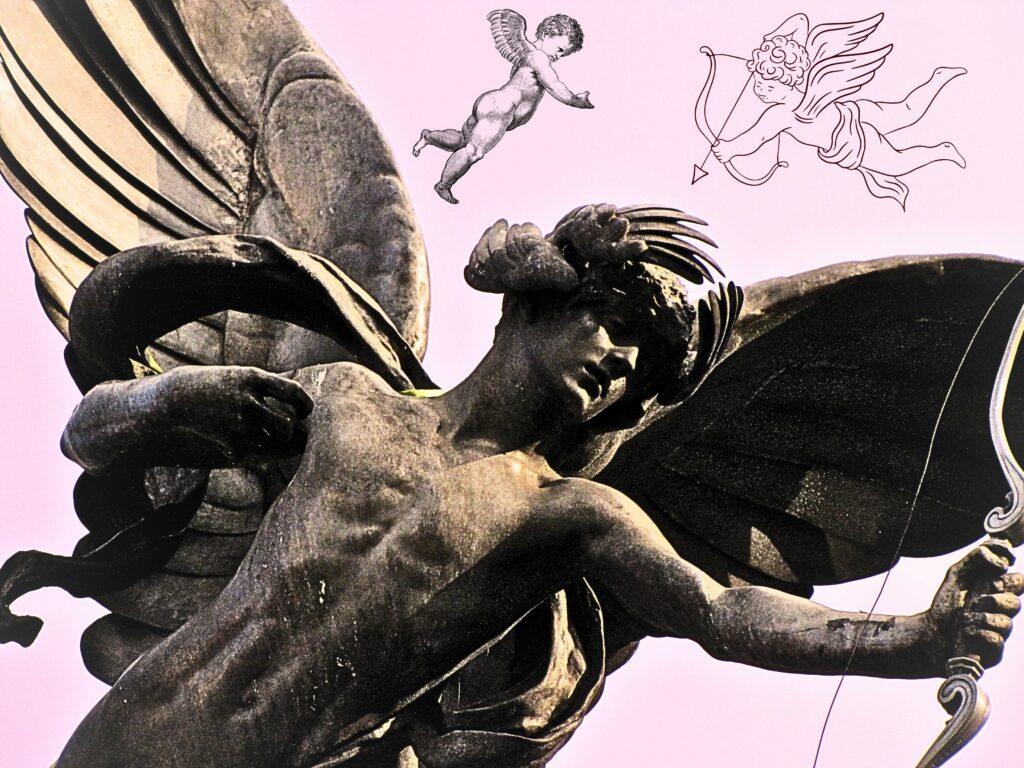

I would be remiss if I did not explore the origins of Cupid himself on Valentine’s Day, especially since tiny, winged babies often flit through the various paper décor one is accustomed to seeing halfway through February. Perhaps those unfamiliar with the myth would be surprised to learn that the Greek version of Cupid is not, in fact, a cherubic baby, frolicking about as he shot his arrows of love into the unsuspecting blessed.

In Greek myth, Eros was the god of love who held dominion especially over the realm of the ‘erotic’. A true lover of chaos, Eros shot his magical arrows at his pleasure to drive people mad with lust, desire, and even love, usually to disastrous results, be it mutual or one-sided. Occasionally, animals would even get thrown into the mix, though cases like this would more often than not be a punishment Eros (or his mother, Aphrodite) had deigned to give. Perhaps this is why love brings us just as much pain as it does pleasure, for Eros’ involvement in mortal lives was extremely chaotic. His very name translates to ‘desire,’ which is no surprise when you think of the madness such desire instills in each of us. It wasn’t until his marriage to Psyche, who would become the goddess of the soul, that the chaos of love was balanced with the equal power of the human spirit, (a fantastic story for Valentine’s Day where love truly conquers all, especially in-laws).

So how do we get a tiny, cherubic baby named Cupid from the god of erotic love and desire? As per usual, the answer lies with the Romans. In an effort to distance themselves from the power love held over humanity, the did the only thing they could: they infantilized him. Where Greeks acknowledged, in spite of themselves, the madness that took hold of humans in love, the Romans sought to reduce his power. Suddenly, Eros-Now-Cupid was merely a mischievous child acting purely on behalf of his mother Venus rather than a powerful and independent god who did what he did for the love of the game, who only occasionally acted on his mother’s behalf. Love was tamed, adorable even, and generally more digestible to a people who invented the philosophy of stoicism. Love was not a punishment or madness, but a pleasant reward delivered to us on tiny baby angel wings that could be ignored if one really tried. Cupid has remained in the popular consciousness ever since as the cherubic figure who delivers sincerity and light mischief rather than the all-consuming flame of love.

Personally, I prefer the chaos of Eros, but that might just be the Greek in me.

Argyrobounialaki

In many countries, proposals look much the same. A man gets down on bended knee to hold out a diamond ring while overlooking the seaside, or the top of a mountain, or wherever a couple’s love holds the strongest memories. Done right, a proposal is a genial memory that perfectly happy couples can look back on with fondness, perhaps especially on days where reflecting on the love they share is encouraged.

But on Crete, sometimes, love can cut like a knife.

Visitors to Crete might be familiar with the significance of the Cretan dagger, which has held cultural importance to the people of the island for centuries. Today, the artisans who still craft these knives authentically are mostly based in Chania, where it may be your only chance to find authentic argyrobounialaki.

For centuries, men on Crete did not propose with a ring, but instead presented their future brides with a small, silver dagger known as an argyrobounialaki. These daggers were small but still sharp, and sometimes engraved with a name or short poem, (with certainly more space than an engraved engagement ring). The future bride would wear the dagger tucked into her sash around her waist for all to see, just like the men of her village would wear their own daggers. The purpose of the dagger was three-fold, the first and most obvious being that it was an outward symbol of the engagement. A ring may not be noticed at first glance, but a knife tucked into a sash is harder to miss. The second, and perhaps more somber reason, was that it served as a reminder to the woman that, should she be unfaithful to her future husband, she would have no alternative but to die, whether at her own hand or at the hands of the man. However, the third reason was an act of empowerment: the bride-to-be was now given the agency to protect herself should she be placed in any danger, and her wearing the knife signified to those who wished her ill that she could and would defend herself.

At times equal parts cruel and empowering, the ceremonial dagger was a staple of Cretan celebrations of marriage for centuries. Though it has since been replaced (for the most part) by the more well-known custom of giving engagement rings, the Cretan dagger has remained an important cultural touchstone in all facets of life, from engagements to marriages, folk magic and ceremonies of all kinds. After all, there’s something about receiving an engagement dagger that makes for a memorable start to a marriage.

February and Valentine’s Day

So why is it that Valentine’s Day falls during the month of February, anyway? I’ve always wondered why one of the coldest months of the year is so closely associated with celebrating love, and more often than not the answer I got was that Lupercalia, the Roman festival of fertility, was celebrated on the modern equivalent of February 15th. However, the ancient Greeks, as seems to be the case, were first to establish the month as a season of love: in their calendar, this seventh month of the year was called Gamelion, and was known as the marriage month. Perhaps because of the proximity to spring, or perhaps because the days were warmer while the nights were cold in this month, but Gamelion, not June, was the month everyone in the ancient world aimed to celebrate their wedding. Today, no wedding on Crete is complete without a fireworks display, which may seem like going all out until you compare it to their Ancient Greek counterparts, who celebrated their weddings for three festive days of partying and making sacrifices to the goddess of marriage, Hera. Though less about true love and more about arranging advantageous connections between families, that didn’t stop the ancient Greeks from throwing the ultimate wedding party.

Perhaps, in that respect, not much has changed for Greece.

Of course, our modern celebration is not due to the timing of Gamelion, but a coincidence. Though St. Valentine is not recognized within the Greek Orthodox church, everyone with a ‘Valentine’ variation to their name still celebrates their Name Day during this time. Perhaps it was fate that the Catholic Patron Saint of Love was executed on February 14th, (though there is more than one Saint Valentine, and the island of Lesbos claims to hold sacred relics of at least one of them), bridging this strange gap across time and religion to cement the month of February as our time to remember the importance of love in our lives.

A strange coincidence, to be sure, but one that certainly gives me pause as to the connectedness of the history of humanity.

In Conclusion

There are many more myths and customs to be explored when it comes to the celebration of love, but for now I shall leave you here. There is much to revisit come next Valentine’s Day, perhaps as many stories and customs are there is love in the world. To you, dear reader, if you’re wondering whether or not to engage in any kind of festivities this coming weekend, go on: read some old love stories, consider some less conventional ways of showing love, and embrace the spirit of the day no matter your relationship status.

Love is more than enough reason to celebrate.

By Katarina Kapetanakis