The words ‘Greek Literature’ tend to conjure up very specific images: Marble busts of Homer and Herodotus that sit in dusty shelves of a library sandwiching well-read copies of The Iliad and The Odyssey with bent spines and dog-eared pages. For some, the first thing that comes to mind is a beaten up school copy of Edith Hamilton’s Greek Mythology annotated with notes from a 9th grade English teacher. Still others think only of the great works of the first philosophers; these are the people who tend to store quotes by Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, and Diogenes in their heads that are then pulled out every so often to spice up a paper or impress friends at parties. Have you guessed what all these people have in common? ‘Greek literature,’ for them, begins and ends in Antiquity.

The misconception about where Greek literature begins and ends begins, for many Americans, in school. The countries you focus on shift in the chronological order of who’s empire collapsed first: Greek, Roman, British, American. Once in higher academia, students have the option of finally venturing into the cloudy world of ‘World Literature.’ This is a catchall term for any countries that aren’t America or England, and serves to lightly, (and I do mean lightly), gloss over literature from countries such as India, Kenya, West Africa, France, Columbia, or Japan. These classes, usually coupled into Levels 1 and 2, are meant to pique interest in the literature from these countries, rather than act as comprehensive lenses into their world. Years and years can be devoted to American literature from the 20th Century alone, whereas one elective class groups Gabriel García Márquez with Salman Rushdie and pats itself on the back. Mission accomplished.

Meanwhile, in the average American bookstore, what gets sold is once again a reflection of the almighty cultural timeline: the American and British greats are well-stocked, from Ernest Hemingway to the latest pulp novel. French authors are more often than not relegated to those published between 1600 and 1800, with a brief burst from the 1920s. Russian literature is often not found except for books from the late 19th and 20th centuries. If you happen to be looking for any authors from any South American country, your local big-chain-bookseller will gladly point you in the direction of 100 Years of Solitude, which you have already read at least three times over. And Greek literature? Well, says the big-book-chain, the latest translation of The Odyssey is right here. Or perhaps, if you’re daring, you’d like to try some Aristophanes.

All of this is to say that I was left with the distinct impression that the world left Greece behind in the cultural literary zeitgeist. This is patently untrue, of course, but it is what most Americans are left believing. How insulting it must be to think that the country that created theater would simply stop creating. The Greek people, and the many facets of their regional identities, did not stop the act of creation just because a continent across the ocean stopped taking notice of them. Greek literature has evolved over the centuries into many beautiful forms, still speaking to the human condition with as much truth and potency as they did 2,000 years ago.

This brings me to the Athens airport circa the summer of 2023. Due to several connecting flights I had not slept in over 24 hours, unable to catch more than five minutes of a blissful computer-like shutdown of my brain while curling up on a bench by my gate. When it became too much for my aching, nearly 30 year old back, I made the executive decision to surrender my seat in favor of window-shopping. On my side of the airport, most of the shops were decidedly out of my price range, luxury brands that were nice to look at but not to touch. What was left to me was a nail salon, food, and the airport bookstore, and as I had another two hours before I was supposed to board my flight to Crete, I figured a little once-over couldn’t hurt. In that moment I both celebrated the mass variety before me and cursed my inability to read Greek. There were swaths of books from every era, especially the postmodern movement, from Greek writers I had never heard of. Poetry books, folklore, dramas, and more were suddenly open and available to me, and I felt myself overwhelmed by the possibility of entering a new world of literature I had never entered. Still, I carefully picked out ones that stood out to me immediately, carefully laying them out in my carry-on bag so I could begin my reading on the plane. In that instant I fell down a rabbit hole, beginning a journey I’d like to share with you now as I take you on a sort of beginner’s course of the importance of Greek literature.

I first learned about the existence of The Erotokritos while sitting on a tour bus in Heraklion, days after my experience in the airport bookstore. Growing up I had a great fondness for ‘The Classics,’ and in my youthful ignorance I assumed I knew all of the important ones, as well as which were ‘worth my time.’ Reading Renaissance literature was a delight for me in college, and though I was in time able to combat most of the erroneous beliefs from my youth, I was still under the assumption that I had a pretty good knowledge of even the more obscure texts. So imagine my surprise when I learned that Crete had contributed the best example of Renaissance poetry that you’ve never heard of.

Written by the Cretan-Venetian noble Vinsentzos Kornaros between the years 1590 and 1610, The Erotokritos tells the story of the love the titular Erotokritos has for the Athenian princess Aretousa. Like the more widely recognized Cyrano de Bergerac, Erotokritos woos the princess by singing beneath her window in the dead of night so he may preserve his identity, and she, of course, falls for him. The king of Athens disapproves of a mysterious stranger wooing his daughter by night, having no knowledge that the man in question is a favored member of his own court. Like many grand love stories of the era, our couple is separated by a murder plot, a time skip, mortal peril, and concludes with our hero testing Aretousa’s love for him with a well-placed disguise and a sincere yet dramatic declaration of love. And to top it all off, this epic poem has a happy ending. Though modeled after the French poem Paris et Vienne, the uniqueness of The Erotokritos cannot be denied by readers. It takes on not just a decidedly Greek interpretation on the value of true love and courage, but is also unmistakably Cretan. The dialect in which the poem is written comes from that island, and even more specifically, from Sitia. If I were a proper linguist, I would delve into the magic that is Eastern Cretan idiom, and how the author’s own Cretan-Venetian heritage influenced which words he used that were derived from Italy’s influence on Crete. This poem went on to inspire the poet Dionysios Solomos, the poet whose work Hymn to Liberty became the Greek and Cypriot national anthem. It inspired countless other poets and Cretan musicians, and was first translated into English by doctor and naturalist Theodore Stephanides, the mentor of Gerald Durrell. This is, by any right, a text that anyone could classify as ‘Important’ with a capital ‘I,’ and yet I’d never heard of it until I decided to take a bus tour on a sweltering summer afternoon.

This period of time is an interesting time for literature. During the same 20 year period it is estimated that The Erotokritos was written, Christopher Marlowe published both parts of Tamburlaine, followed by his adaptation of Doctor Faustus two years later. Edmund Spenser published books 1-3 of The Fairy Queen. Shakespeare’s Hamlet premiered to critical acclaim. Miguel de Cervantes published both parts of his epic Don Quixote, with a ten year gap in between each part. This small slice of the Renaissance produced immortal works that now permanently live on the periphery of our cultural knowledge. Even if you’ve never read these stories, you know enough about them to understand their importance, you know enough about them to understand the in-jokes. Why, then, is this seminal work of Greek (and, especially, Cretan) literature left out of the commonly taught canon of Renaissance literature? Why keep alive the Greek myths and stories from antiquity, but not this? Is it somehow less accessible or relatable than Don Quixote? Is it less emotional than Hamlet? Perhaps if a Disney executive or a Broadway producer had read it and slapped some show tunes onto it, more of the West would widely recognize this work. But it’s for the best, I think, that The Erotokritos remains a hidden gem waiting to be discovered by new readers, preserving its own deeply entrenched musical tradition as it continues to inspire poets, writers and musicians alike just the way it is.

Nikos Kazantzakis is perhaps the only name I’m going to reference that you might recognize. His two most famous novels, Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ, have been adapted into critically acclaimed films that most American audiences would have a tertiary knowledge of. The film starred Anthony Quinn as the titular Zorba, and his interpretation left such a lasting impression that there is now a beautiful beach in Rhodes that bears his name. Cinephiles, at the very least, would probably recognize iconic dance scene in Zorba where, at the very end of the film, the titular Zorba teaches Greco-British Basil to dance in a final expression of mad exuberance. Out of context, this scene has been referenced and parodied to death, but within the film the dance expresses a bittersweet testament to the fickleness of life. I’ve been to the beach where they filmed portions of this movie. I swam in the water and looked up at the cliffside, I ate at a taverna just down the street from where Anthony Quinn stayed during the shoot. And yet, before this trip, I had not read a single thing by Kazantzakis. The novel is just as powerful, if not more so, as Kazantzakis’ prose elevates the story to a higher level. I found myself charmed and infuriated by the boisterous Alexis Zorba as much as Basil was, and the ending of the book was more emotionally potent than the movie had been, leaving me with an almost empty feeling I sat with for quite a while.

The Last Temptation of Christ was one of many of Nikos Kazantzakis’ explorations into faith, who Christ was, and what it all meant to be ‘Christ-like.’ The story goes into what it means to actively choose to assume the role of Messiah, what a normal life for Jesus could have been, and what surrendering to God’s will and ultimately rejecting the ‘last temptation’ meant. It is considered to be the most controversial work Kazantzakis wrote, as well as his most deeply spiritual, and for it he was excommunicated from the Orthodox faith. Audiences today still seem to miss the point of the work, with every facet of Christianity protesting not only the book itself but the film adaptation directed by Martin Scorsese. Like Kazantzakis before him, Scorsese was met with death threats, and the film is still banned in certain countries around the world.

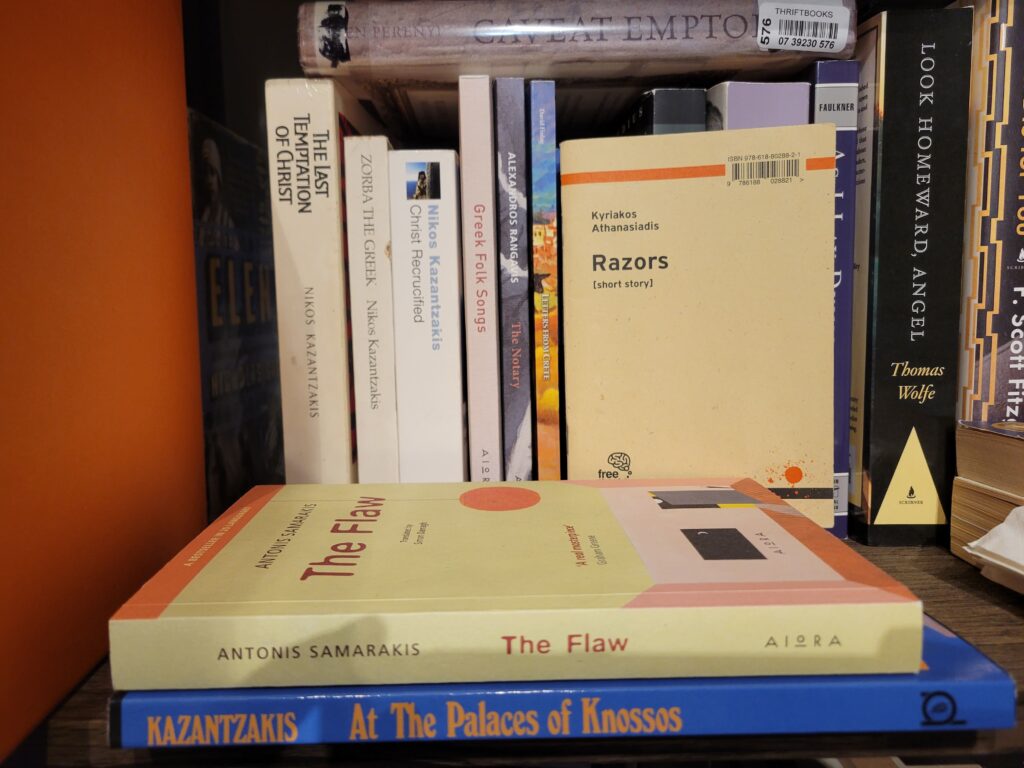

Kazantzakis wrote 6 travel books, 15 novels, 8 plays, 2 poems, and 14 essay collections and memoirs. I have named 2 books. Two, out of his entire bibliography. I had no idea, before traveling to Greece, they even existed. I knew of Zorba and Last Temptation from an early age, and the copies of the books I own were easy enough to find. But I recognize that I am not the standard: many of my friends didn’t even know Zorba was a film, let alone a book. They assumed it was simply the name of a song. Kazantzakis’ work has been very important to me, and when I found the rest of his bibliography in a small bookstore in the port of Chania, it took everything I had not to walk out with every single thing he had ever written, at least those translated into English. Christ Recrucified, the story of a small town attempting to put on their annual Passion Play, is a powerful story about what a religious ritual means to a place under occupation. At the Palace of Knossos is a retelling of the myth of the Minotaur, but it examines it as metaphor for failing empires and colonialization. After all, the island of Crete was once its own mighty empire that, after natural disasters and apocalyptic events, became Greek. I have yet to work my way through all of the books I purchased, but each one connects with me in new and unexpected ways. There is something profound about his prose and the questions he dares to ask that are so quintessentially Greek, so quintessentially Cretan, that I cannot help but feel an attachment to him.

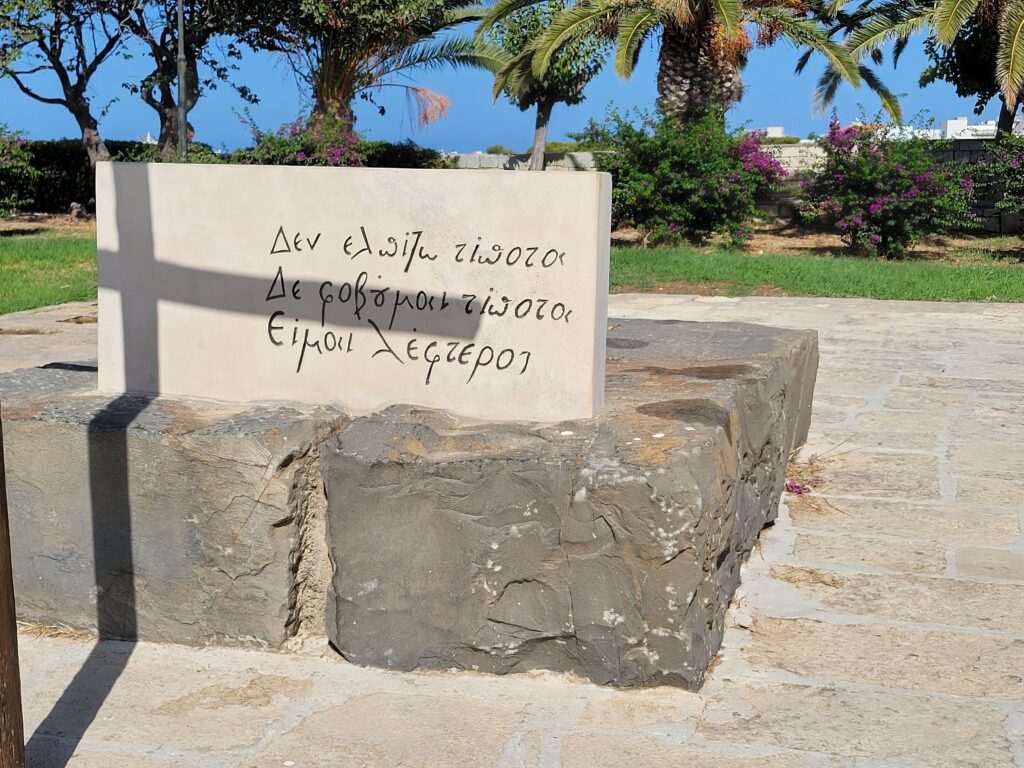

I visited his grave at the top of a hill that overlooks the city of Heraklion. I had never been before, in all the visits I had paid to the island, but something about this trip made me feel that it was finally time. It isn’t in a place you’d expect there to be a grave, and the walk up the hill is at time a little strange as you pass through well-paved but heavily graffitied stairs. The site is not hallowed ground, but as I stood in the quiet, staring at the large stone slab marking the place where he was buried, I could not help but feel that the place had a kind of serenity to it. Nikos Kazantzakis’ gravestone reads “Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα. Δε φοβούμαι τίποτα. Είμαι λέφτερος.” Translated, it means “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.” Though scholars have stated (and I am sure they’re right), that Kazantzakis meant his epitaph to be a larger reflection of his cynicism, I could not help but view it in an almost Buddhist lens: I have no expectation, and so I am free of it. I am at peace. I stood on the top of that hill, silently watching as the wind blew through the trees, coming as close to meditation as I ever have, and as close to a communion as I could have in several years. I don’t know if he would have approved of me treating his resting place as something sacred, but I couldn’t help but feel as if, despite the lack of a blessed resting place, there were clear traces of a kind of divinity.

I came across Antonis Samarakis’ The Flaw in that airport bookstore, hooked by the title that both intrigued me and made me wonder, ‘the flaw in what?’ The answer to that question is a sucker-punch to the gut, and one that made me seriously consider what it means to live freely. Set during a time of an unnamed fascist regime, The Flaw follows three characters set on a collision course that results in an over-the-top plan to cause one of them to confess to belonging to the opposition. We never learn what ideals the regime holds up. We never learn what exactly the opposition is working for, except of course to be in opposition to the regime. What see are glimpses into the humanity of the characters as they desperately try (and ultimately fail) to remain nothing but cogs in their respective machines. The Flaw is not an easy read: from jumping timelines to constantly shifting viewpoints, it is a book that one must pay their full attention to. The payoff, however, was one of the most satisfying things I’ve read in years, and left me with the bittersweet revelation that all totalitarian regimes like this are doomed to fail, so long as humanity endures. It was a powerful piece of literature that was a haunting prediction of the real-life Metaxas regime that took over Greece in 1936. Perhaps Samarakis saw the writing on the wall where he saw his country headed. Perhaps it was a general warning to the world to be wary of the rise of totalitarianism. Either way, the novel serves as a timeless testament to the power of a human bond, and how as long as we are able to recognize each other’s inherent humanity, there will always be a flaw in the regime.

After I finished reading this book, I turned it over to give the cover another glance. The edition I grabbed was the fiftieth anniversary edition, its minimalist design of the cover adorned with a snippet of praise by author Graham Greene. ‘Graham Greene?’ I thought. ‘Leading voice of the 20th Century Graham Greene? Author of Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, and The Third Man Graham Greene?’ I opened the front cover to find further glowing reviews from other authors I knew: Arthur Miller of The Crucible fame. Agatha Christie, Queen of the Detective Novel. I looked briefly at my new copy of Kazantzakis’ Christ Recrucified to see praise from Thomas Mann, author of the well-known Death in Venice. All these authors I grew up studying, respecting, admiring even, were paying their respects to Greek authors who I either knew the bare minimum or nothing. Where was the justice in that? Why were these stories widely circulated enough in these authors’ times, but not mine? I still don’t have an answer that satisfies me. Yes, at the end of the day, books are a commodity: books that make money continue to be printed. Books that do not are retired to the dusty shelves of a used bookstore that may or may not carry what you seek. I understand this is the way of things. But perhaps, if this mindset of what we value in literature could change, then maybe these important novels have a chance of staying relevant longer than the latest fantasy romance novel that has TikTok in a chokehold.

If you’ve stuck with me up to now, you may be asking yourself: what on earth does this have to do with travel? That’s a fair question, and most people who read this blog would generally prefer I’d stick to talking about beaches and historical points of interest, (which, in my defense, I mentioned one or two). But think about this: every time you’ve gone somewhere new, you’ve researched the language. ‘Where is the bathroom?’ ‘Can I get the check?’ ‘Where is the library?’ You do it as a courtesy to the people whose land you are visiting. You do it to serve as an outstretched hand, to show you are willing to go a step further to bond with a fellow human being, to prove that we have more in common than we have differences. Literature, especially literature created by and for the people of a place you plan to visit, adds a very important layer to travel. It adds an insight into the cultural mindset of a place, what art they find important enough to treasure and what values they uphold. Art is not and should not only serve as inspiration to travel. Art is why we travel.

So the next time you click ‘book’ on your travel website, take a moment to look up the writers, the poets, and the playwrights. Pick a short story or a poem. Read it carefully until it digests into your bloodstream, until you can hear the soul of the place calling out to you from within yourself. Take it with you when you go.

Rinse and repeat.

By Katarina Kapetanakis